The effects of underwater electrolysis and the corrosion damage it can cause to metallic boat parts have concerned boaters for many years.

In more recent years has it been proven that these same factors can have a significant role in how a boat fishes.

This chapter describes a step-by-step procedure that you can follow to see if your boat is adequately protected from galvanic corrosion (electrolysis) and is set up to maximize the positive effects of a positive voltage on fish.

A voltmeter with a scale of zero to one volt will measure the natural voltage of your wire. Here the natural voltage reading is .782 volts. Note the positive lead is touching the down-rigger wire. The negative lead is connected to the engine or the negative pole on the boat battery.

By following these steps carefully you can save yourself a lot of grief from corroded boat parts and may considerably enhance your fishing results.

Whenever a boat is in water, the different underwater metal parts interact with each other to form a weak battery. Electrical currents flow from one metal part to another depending on the type and placement of the metals involved as well as the mineral content of the water. Typical metals used on boats include aluminium, copper, steel, brass, stainless steel and zinc as sacrificial anodes.

If a boat is set up properly all the corrosion is channelled so it dissipates harmlessly in the zinc sacrificial anodes. As it does so, it creates a positive field around the vessel which can be helpful in attracting fish.

“Albatross Marine-Electrics” Quick Boat Check Procedure.

1. Use a voltmeter that has a DC scale that will read zero to one volt.

2. With the boat in the water, lower a down-rigger wire into the water five or six feet. It is best to do this away from marinas or docks where a number of boats are moored. Stray electrical currents from battery chargers or electrical systems can distort your readings. It is also best to have a vinyl-covered down-rigger weight and an insulated end snap connecting your weight to the wire.

3. Turn off everything electrical on the boat. Turn off the master battery switches if you have them. Then connect the negative lead from your volt meter to the negative battery terminal, the engine or to some other grounded metal on the boat. Touch the positive lead to your down-rigger wire near the spool or along the arm. You should get a natural voltage reading of between .7 volts and .8 volts. If the reading is significantly outside this range, you have a problem (see later problem section).

4. One by one, turn on the boat’s different electrical systems and watch the voltmeter. Start first with the battery switches. Next, turn on the bilge pump. Start the engine and then each of the other electrical devices. If your natural voltage reading changes by more than .05 volts from its starting point with any of these steps, you have an electrical leakage problem. These are quite common in battery switches and accessories like bilge pump connections where a slight amount of positive electricity can leak into the water in the bilge.

If your boat fails test 3 or 4, you are probably repelling fish rather than attracting them. You need to find the problem on the boat and clean it up.

Initial things to check if your readings are not normal…

If your readings are low (below .500) most of the time the problem is either your zinc not making good contact with the water or your down-rigger cables are not making good contact with the water. Boats that are kept on trailers out of the water, often get oxidation on the zinc and it will become covered with a white powder. This insulates the zinc from the water and causes a low voltage reading. The solution is to clean the zinc with a stainless steel brush.

Down-rigger wires also get corrosion and don’t make good contact with the water. The older the down-rigger wire, the more likely it is covered with scum or corrosion. It will give you a low reading even with a good zinc. For testing purposes you can scrape or clean a section of the wire with steel wool. If the wire has broken strands it’s probably time to replace it. Different down-riggers on the same boat will frequently show different natural voltage readings because the wire on one will be older or more corroded than the other.

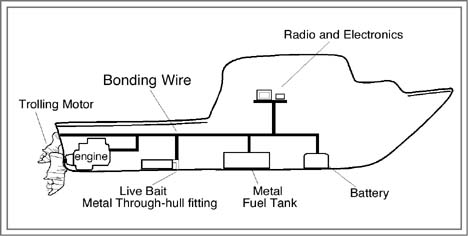

Boat bonding could be a problem. Inspect the inside of the hull. If the boat is fibre glass or wood, there should be a copper bonding wire running along the bottom of the hull connecting all the underwater metal fittings together. For example, it should run from the engine or outdrive to the metal fuel tanks, metal water tanks, thru hulls, trim tabs and motor shaft and stuffing box. Be sure the bonding wire is not broken and that the connection to each fitting is clean and tight.

The connections are easy to check with a volt/ohm meter. With the boat in the water, touch the positive lead from the volt meter to each fitting and the negative lead to the bonding wire. If the meter shows a reading of .010 volts or higher, clean the connection and recheck. If it’s below .010 volts, check the same connection with an ohm meter to ensure continuity of less than one ohm. If the boat is out of the water on a trailer, you can use the ohm part of this test by itself.

If your outboard engine is an electric start, it is automatically grounded and nothing further needs to be done. If it is not an electric start it must be grounded (bonded) to the boat ground system. This can be done by running a wire from the metal on the motor to a ground point on the boat hull. If you are not sure the motor is grounded, you can use a volt/ohm meter to check. To test for bonding, connect the negative meter lead to the negative terminal of the battery and test for continuity to the boat hull or bonding strap as well as the outboard motor. If there is no continuity, install a bonding wire (#10) from the negative terminal to the hull and to the outboard.

A common problem occurs with auxiliary outboards that are not electric start. Unless this motor is bonded (connected) to the ground part of the boat, the zinc on the auxiliary will create a strong positive field around the boat (“hot boat”). This can severely impact your fishing results.

Another common problem is separate batteries in the boat that are not grounded to the main battery. Many fishermen will install a separate battery to run accessories like electric trolling motors, depth sounders and radios. The negative ground terminal on this battery must be connected to the negative terminal of the main boat battery or you may be creating significant fish problems.

Electrical leakage of positive voltage from a battery switch or, bilge pump or another positive terminal can also cause a major problem and a “hot boat”. Positive leakage will cause a higher than normal natural voltage reading in your boat test. If your reading was more than about .750 volts, you probably have leakage.

For each volt of electrical leakage you will read approximately .120 volts of higher natural reading on your down-rigger cable. For example, in step 4 of the Quick Boat Test Procedure, if you read .200 volts more on your down-rigger cable when you turn all the boats electrical systems on, this means you are leaking approximately .200/.120 or 1.67 volts into the water. You need to find and correct the leak.

Leakage of electricity from the plus side of a boat’s power system creates “hot spots” and will ruin a boat’s fishing ability. Here an isolated screw on a battery switch shows a leakage reading of .59 volts. This charge will pass along the fiberglass, through the bilge and directly into the water around the boat. This switch needs to be removed and all surfaces cleaned free of the dirt and crust that are allowing the electricity to pass.

Leakage of electricity from the plus side of a boat’s power system creates “hot spots” and will ruin a boat’s fishing ability. Here an isolated screw on a battery switch shows a leakage reading of .59 volts. This charge will pass along the fiberglass, through the bilge and directly into the water around the boat. This switch needs to be removed and all surfaces cleaned free of the dirt and crust that are allowing the electricity to pass.